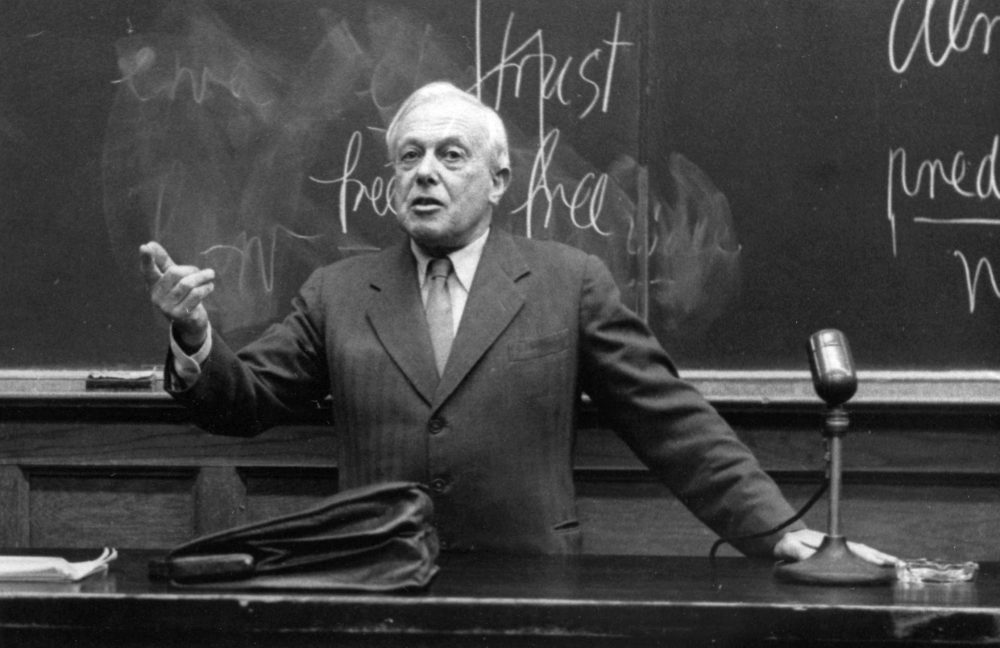

Volume 20: Historiography (1959)

Thirteen 2-hour lectures.

Why do we sit here, sir? It only makes sense because you are responsible that all the future that already got started in Pericles must not be destroyed and omitted by you, you see. The future has already begun yesterday. The good future, the vital future has now of course its mainsprings already somewhere in the past.So you-we study history lest some part of the future, you see, that already started a thousand years ago, be omitted.

—May 4, 1959

Rosenstock-Huessy begins by defining history as a religious act, the declaration of the common origin and the common destiny of mankind. In history, the past is seen in the light of the future; the historian is the healer of conflicting memories who keeps alive the memory of the sacrifices that purchased our freedom (in contrast to the philosopher, who would strip truth of its human context in time).

Rosenstock-Huessy spends most of the course using the histories of the ancient world to illuminate our situation today. He contrasts the Bible’s approach to events with that of pagan histories; the Greek urge to classify is set against the Jewish and Christian urge to name.

While honoring Plutarch, he shows that the Lives are premised on constancy of character through events, and thus concerned with being. The Book of Samuel, on the other hand, is premised on promise and fulfillment, and thus concerned with the process of becoming. History is a function, not a label, and so is to be found in all genres; Rosenstock-Huessy passionately defends poetry as a type of vision necessary to human existence, and as a vehicle for history.