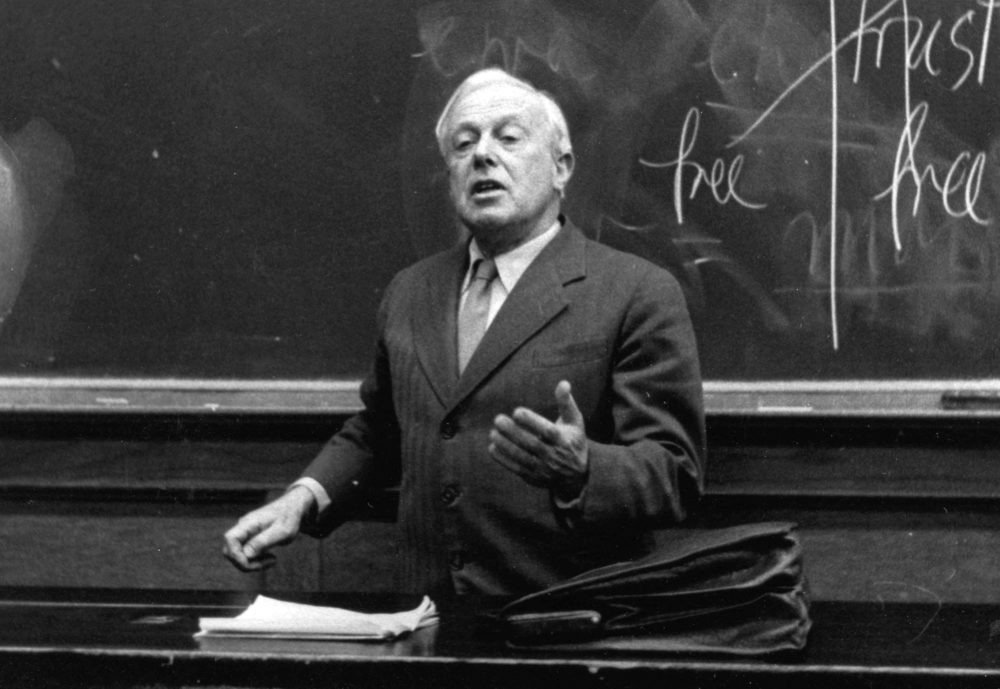

The mind of the people in this country has never wanted to live through the two extremes of war and peace. But only in alternation, that there—people were very brutal in wartime indeed, and that they were very sweet and pacifistic in peacetime. But this isn’t the problem. You have to be a warrior in peacetime, and you have to be peaceful in wartime. That is the moral problem of mankind, if you want to comprehend our undertaking as human beings.

—March 25, 1959